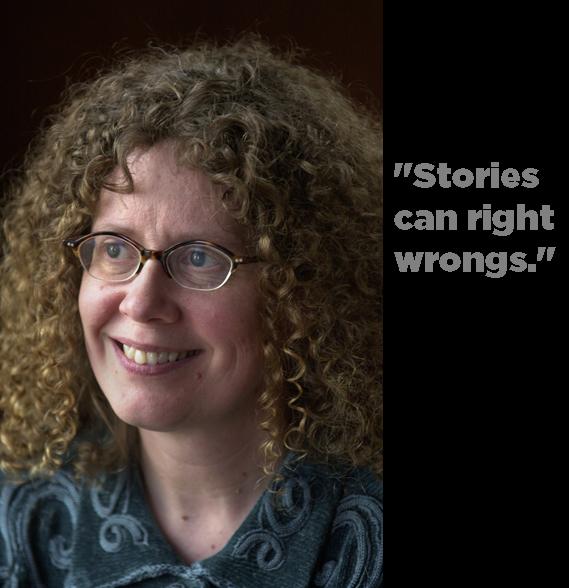

Laurie Hertzel este Senior Editor la Star Tribune, in Minneapolis. Noi am cunoscut-o anul trecut, la The Power of Storytelling Conference, organizată de prietenii de la Decât o Revistă. I-am povestit lui Laurie despre Premiile Superscrieri și i-a plăcut plăcut inițiativa, așa că a scris un articol special pentru voi, cei care credeți în puterea poveștilor. Sperăm să vă placă și să vă dea o scânteie pentru a vă aprinde și vouă pofta de a vă scrie poveștile despre realitate. Nu de alta, dar duminica asta, pe 30 septembrie, se închid și înscrierile în concurs. Așadar, spor la inspirație și la idei!

We first hear stories while still in the cradle. Our parents read us bedtime tales at night; we hear parables at church; we learn to read by turning the pages of picture books and sounding out the text. Our lives start with story, and story follows us throughout all our years. Stories mark significant occasions – weddings, holidays, anniversaries, reunions. At our funerals, people will gather to remember us, and to tell stories. (Hopefully, good ones.)

We tell stories to make sense of the confusion of our lives. We tell stories in order to keep our history, to understand the things that happen to us, and to help others understand us. Human beings are hard-wired to tell stories – all of us. You will not find a culture that doesn’t have some sort of storytelling tradition.

In journalism, stories carry a particular power because they are true. When you tell a story to a friend over coffee, you might embellish for drama’s sake, or exaggerate for the sake of humor, or to sway someone’s point of view. But in journalism, the power is in the truth. Journalists tell true stories, reported carefully and fully, and retold accurately, with enough detail and action so that the reader can see into someone else’s life.

Through the stories you write, you can give readers a taste of other people’s lives. You can put readers where they might not otherwise ever be able to go. You can place the reader in the middle of a terrible storm. You can make the reader feel like he is in a battle in the mountains of Afghanistan, or fighting a four-alarm fire burn a house in a quiet suburban neighborhood. You can place your reader in a wheelchair and make him understand what obstacles a handicapped person might encounter in the course of a normal day. You can take the reader on a hiking trip through the hills of Ireland, or on a fishing trip in northern Minnesota. You can entertain, enlighten, frighten, outrage, amuse, educate and enthrall, with stories.

It is heartening to see new prizes, such as the Romanian Superwritings Prizes, being created to recognize and honor great storytelling. In the United States, of course, the highest honor for journalists is the Pulitzer Prize, and world wide the highest honor for writers of nonfiction is the Nobel Prize. Here is hoping that the Superwritings Prizes comes to stand for journalism and storytelling of the highest caliber in Romania. It is important to recognize this good, vital work.

In old Ireland, Seanachies – the traveling storytellers – were revered and welcomed wherever they went. They sat by the fire of the houses they visited and everyone from the countryside gathered to listen as they told stories about Irish history and legend, and immortalized its battles, and secured the reputation of its kings.

Newspapers and magazines now serve as sort of modern – day Seanachies. Open your newspaper and you will see that it is filled with stories, or the skeletons of stories, potential stories – stories about real life, stories about things that happened in your country, your town, to your neighbors, and it all happened just yesterday! And more incredible stuff will happen today! All kinds of fascinating and controversial and tragic and funny and dramatic and dire and life-changing event – murders and car crashes and burglaries and weddings and festivals and floods and blizzards and people helping each other out during floods and blizzards.

When the Interstate 35W bridge in Minneapolis collapsed over the Mississippi River at rush hour four years ago, dumping cars into the water and killing 13 people, my newspaper covered that story in a multitude of ways. We wrote the usual news stories, and we spent months doing investigative pieces, trying to understand why the bridge fell, and trying to figure out who was to blame. But we also wanted to tell the stories of the people who were on the bridge during that evening rush hour and who rode it down to the water. We wanted to put our readers right on that bridge, and make them feel what those survivors felt. Those stories, those narratives, were among the most powerful stories we published.

A well-told story brings us from the intellectual – what happened – to the emotional – what did it feel like? Who was affected? And the most powerful of all stories marry the two. Stories are filled with little strings that connect us to each other, and so to meaning.

Stories can right wrongs. They can help people understand a complex topic. They can make people empathize with those they thought they had nothing in common with. They can make people laugh, or cry, sometimes both in the same story. They can make people feel outrage, or compassion, or disgust, or love. They can spur people to take action.

There is no secret to writing great narrative. It takes hard work, and practice, and diligent, dogged reporting, and an understanding of the craft of writing. All of the basics of good writing that you learned years ago – show, don’t tell; use powerful verbs; let the story spin out; control the voice and pacing; end your sentences and paragraphs and sections and the story itself on powerful thoughts; use telling details – all come into play here. You get good by writing and writing and writing, and by reading and reading and reading.

The biggest challenge sometimes comes in identifying the story itself. They are everywhere! Open your mind and your eyes. Go find them, and tell them.